Western tradition is to work and then retire.

You spend 30–40 years in a job and earn good money. If you’re lucky you’re happy with your life and go on vacation twice a year.

Then you retire and spend your time at home, in the garden, or move to a foreign country to spend your money.

But you stop doing meaningful things.

Although, most people do.

Not in Okinawa, Japan — a place known as one of the “Blue Zones”.

People live significantly longer here.

They have a purpose in their life and they don’t retire. The concept of “retirement” doesn’t exist here.

They found their Ikigai — their reason for being.

The 4 Fundamentals of Ikigai

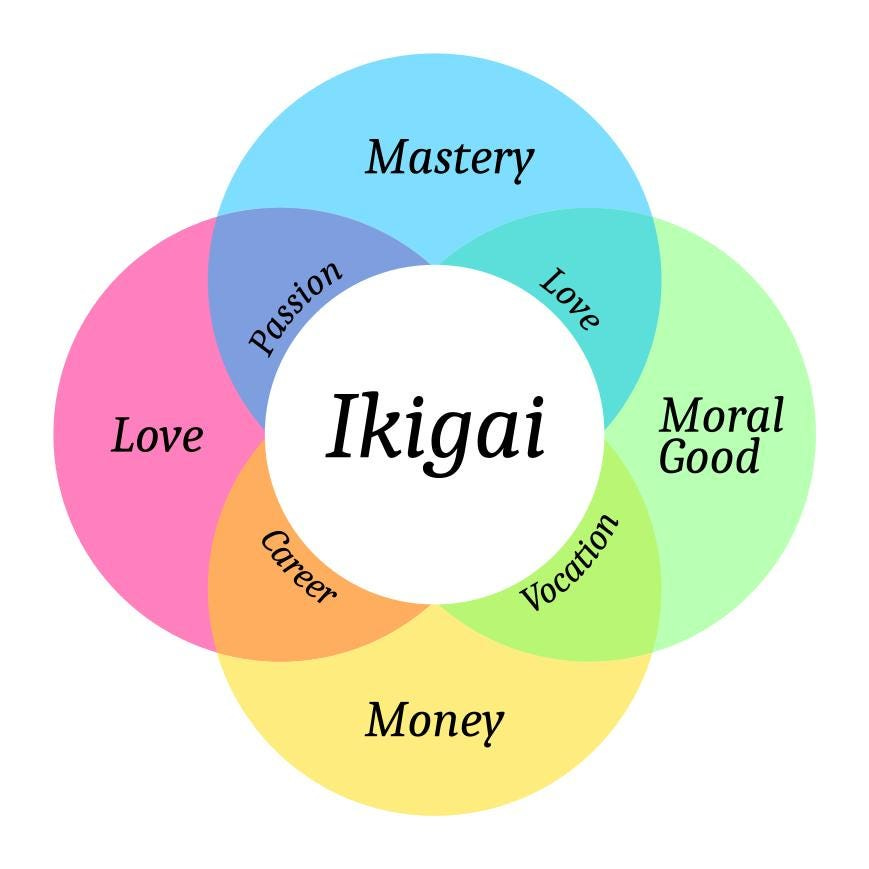

In the concept of Ikigai, 4 major elements combined represent the recipe for a meaningful life:

The things you love.

The things you are good at.

The things the world needs.

The things you get paid for.

Sometimes these 4 things align, that’s when you’ve got everything in the right place.

Then you have a great purpose.

And you feel meaningful.

That sounds like something really good, and something that everybody wants to achieve at some point in their lives.

But it isn’t easy, and not for everybody — unfortunately.

You’d be in the middle of this Ikigai diagram.

Most people strive towards getting a lot of money, and sometimes love that will keep them away from the other 2 elements because they take so much time.

But mastering something you love doing is as important.

And don’t forget to keep your moral standards high. You don’t get eternal satisfaction for doing immoral things that pay well.

Avoid that stuff.

There are a couple of cross-overs in the image that demonstrate this:

love — vocation: to be morally good

career — vocation: to bring in money

career — passion: to satisfy yourself careerwise

passion — love: love should be passionate

And therefore they shouldn’t be their opposites.

You don’t want your love, or vocation to be immoral, so make sure your career path brings in enough money, you should be passionate about your career, and of course love.

When you align these elements right, you’re on track to find your Ikigai.

The Way Ikigai Increases Life Expectancy

Ikigai originates from the Heian era in Japan (around 794 to 1185).

This classical period in Japan illustrates perfectly how people saw life back then. Their cultural traditions and spiritual practices emphasize the balance between the self and the community, and the interconnectedness of all life.

The word Ikigai means “life worth”, that’s a quite literal translation.

But it makes it clear.

Your life should have worth, especially when you live for a very long time.

That’s what people in the Okinawa area are very good at.

People here live longer, and much healthier than in other parts of the world where life expectancy is often below 80 years.

For example, in the United States, men on average don’t get older than 75, whereas people in Japan are at least 10 years older. That’s quite a significant statistic.

When we zoom in even further, to Okinawa, people reach around 83 years and these people are often very engaged in communities and still do a lot of activities.

They don’t stop doing what they love, why would they?

Famous movie director Hayao Miyazaki from the Ghibli Studio movies retired a couple of years ago from filmmaking — but he didn’t stop making art.

He still goes to the office every Sunday to draw.

Research believes that this life expectancy is due to a strong sense of Ikigai that is present in this area.

Physical and mental health is very important to the people there.

The Mental and Physical Side of Ikigai

Stress is a factor that makes us die so much faster.

It’s called the silent killer for a reason.

Ikigai tells people to engage in certain activities that reduce stress — this could be meditation, but it is also one of the 4 core elements that I mentioned.

You have less stress if you make money from something that’s also your passion.

Having financial stability, which makes you able to do the things you love, in general, gives you less stress.

Meditation allows you to reflect on yourself and your soul.

After a day of hard, but rewarding, work you want to get a moment for yourself to discharge and relax. Get a comfortable seat and close your eyes for breathwork for a moment.

You’ll feel reborn and ready to continue with your day.

That’s something the Japanese that practice Ikigai do a lot as well — they’re very conscious, and that’s something we could adapt to our lifestyles as well.

We’re all so rushy.

We don’t take our time to stop and watch a bird sit in a tree, wash itself, put a stick in his nest, and continue with his food search.

We should because life is beautiful.

Then there’s the physical side of Ikigai. Most older people in the Okinawa area are still quite fit for their age.

Moderate exercise, such as gardening or walking is perfect for keeping the body active and improving your cardio and flexibility.

And these people don’t eat too much.

They eat until they’re around 80% full — that’s enough. You don’t want to exhaust your body with all the food you give it.

Enough is enough.

If you take these practices and customs into use for your own life, you might get a little older, happier, and more fulfilled.

Final Thoughts on Finding Your Ikigai

Ikigai isn’t just a method or a philosophy — it’s a lifestyle, a way of living.

It integrates passion, mission, profession, and vocation and it’s a path to living a meaningful, fulfilling, and preferably long life.

The core sense of Ikigai lies in the balance of these 4 elements.

In contrast to the traditional Western way of living, Ikigai suggests to keep doing what you love, to stay engaged in a community, and to fulfill your passion.

It can be a complex journey to find your Ikigai, but it’s a rewarding one.

Simple truths are the best. Thanks for a great article and message, Bryan.

I can endorse the art of ikigai as a way of living life. Now in my 84th year I am getting close to the end of it.

I have no intention of retiring. Graduating in Medicine I was gifted the wonderful ability to earn enough to live on in a relatively short period of time, allowing me to become my own patron of my art as a sculptor.

Early in my life I set the objective to exist in the state where everything I do is work and nothing feels like it. Some things I am paid for and somethings I am not. (I haven't found anyone to pay me for having a siesta yet, but that is working on having energy for the next part of the day)

I am still practicing medicine and loving it. In fact I am entering a new special area in which rather than extending my patient's lives I am guiding them towards a fearless end to it.